WRITING IN NDYUKA-TONGO A CREOLE LANGUAGE IN SOUTH AMERICA

By: Andre R.M. Pakosie[1]

COPYRIGHT: This article was previously published by me in the Maroon journal SIBOGA, Volume 13, No. 1, 2003. All my articles are protected by copyright. No article written by me may be reproduced or published, in whole or in part, in any form whatsoever without proper source citation.

This article is one of the two papers that I presented at the conference ‘Ecrire Les Langues de Guyane’, held in Cayenne , French Guiana from 9 to 11 May 2003 , and published in the magazine for Maroon culture and history, SIBOGA, volume 13 nr. 1, 2003. The conference was organized by the Laboratoire des Sciences Sociales IRD Guyane, concerning the languages spoken in French Guiana. My paper includes the following items: the history of the Maroon languages, writing in Ndyuka, ideophones, changes and difficulties if you don’t have knowledge of the Ndyuka language. Ndyuka tongo is the language that is spoken bij the Ndyuka or Okanisi, a Maroon group of Suriname.

Participants at the conference in Cayenne (Foto: André R.M. Pakosie)

A language is one of the means to unite people. A person will feel quite at home in a country, if he can speak and understand the language that is spoken. He will not feel himself an outsider. When a child is born, the first language he will be confronted with is the language that is spoken by the midwife and her assistants. But the language in which the child will learn to talk and think is the language of the mother, or the language of the person who will bring him up. This language will be the native tongue of the child.

1. HYPOTHESES

There are various hypotheses that the Afro-Surinamese languages, such as the Maroon native languages Ndyuka (Okanisi), Saamaka, Pamaka, Matawai, Kwiïnti and Aluku, and the Sranan-tongo (a lingua franca, mostly spoken by the Creoles), originated in Suriname itself. However, history shows that these languages began in the depots in Africa where European slave traders brought thousands of Africans together for transportation to slavery. The Afro-Surinamese languages are languages, which linguists classify among the Creole languages. They are in origin artificial (Pidgin) languages, in other words, which arise through trade contacts. Languages, which originate and develop through the meeting of groups of people who cannot understand each other (Pakosie, 2000-2:2-12 and Pakosie, 2002:121-131).

An example of a Pidgin, was the so called ‘Businengee patuwa‘, derived from the ‘patoi’ (Guianais) a Creole French. The Businengee patuwa was made by the French Creoles and the several Maroon groups to communicate with each other during the ‘Bagasiten‘ (the period of cargo transportation to the inlands of French Guiana and Suriname ). Nowadays there are few people who speak and understand the Businengee ‘patuwa’. The present-day Maroons who are domiciled at a French speaking area, prefer to learn French directly.

2. INSTRUMENTAL AND VOCAL LANGUAGES

This article primarily concerned one of the Maroon native languages, the Ndyuka-tongo. For the sake of clearness when we talk about Ndyuka-tongo, we have to divide this language into two main groups: Vocal languages and Instrumental languages. The following languages of the Ndyuka are numbered among the vocal languages: (the present-day) Ndyuka-tongo, Loangu, Anpuku, Papa, Kumanti, Amanfu and Akoopina. The instrumental languages include: Wanwi-apinti, Kumanti-apinti, Kwadyo, Agbado, Benta, (Botoo)Tutu and Abaankuman. Abaankuman is a sound or tone code language, related to particular events. For example, in a traditional Maroon society, the sound of a gunshot means that game has been caught, so there is meat to be had. The sound of a bell, a hollow metal object with a clapper that produces sound, indicates that a public worship service is in progress (Pakosie, 2000, 2:2, 12; Pakosie, 2002, 121-131).

Participants at the conference in Cayenne (Foto: André R.M. Pakosie)

3. THE ORIGIN OF THE MAROON LANGUAGES

The contemporary Ndyuka language differs significantly from the language spoken in the earliest phase of the Ndyuka community. Historical sources indicate that the enslavement of black people in Suriname began in 1650, which is 375 years ago. In that year, Western Europeans, including the English, Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese, began trading thousands of black people as commodities in the transatlantic slave trade. These individuals were captured in various regions of Africa and then deported to Suriname and other areas in South and North America.

When we talk about Africa, we are talking about a continent with different countries and peoples. Each people and each ethnic group has its own culture and language. One group does not understand the language of another group. The Europeans kept people from all these different ethnic groups captive in depots. One of these depots was Saint George d’Elmina Castle on the coast of present-day Ghana. The ancestors of the Afro-Surinamese people were held captive in these depots for weeks, months, sometimes even years, before being transported to their final destinations, the slave plantations of Suriname and other places in South, Central and North America (Pakosie, 2000-2:3 and Pakosie, 2002:125). We can safely say that the enslavement of the African people who were transported to South, Central and North America began from the moment they were held captive in the depots. From that moment on, they were no longer free to do as they pleased. The West-European slave traders controlled their entire being.

Precisely in such circumstances, the need to communicate with each other was urgent. This situation forced the captive Africans to create a new means of communication. In this way, a new language originated to overcome the Babylonian confusion of speech created by the enforced togetherness of the ancestors of the Afro-Surinamese people. This new language was composed of words derived from the languages of the captured African people from various ethnic groups. This implies that its origins lie in African languages. For convenience, I refer to this new language as AFRO-AFRICAN (Pakosie, 2000, 2:2, 12; Pakosie, 2002, 121-131).

In addition to Afro-African, a second new language emerged through language contact between the captured African people and the Western European slave traders. This language consisted of words from European languages, words from the native languages of the various captive African people, and words from Afro-African. I call this second language AFRO-EUROPEAN or EURO-AFRICAN.

These two languages, AFRO-EUROPEAN (Euro-African) and AFRO-AFRICAN are the origin of the present-day Afro-Surinamese and Afro-French Guianese languages, such as Sranan-tongo, Ndyuka-tongo, Saamaka-tongo, Aluku-tongo, Pamaka-tongo, Matawai-tongo and Kwiïnti-tongo (Pakosie, 2000-2:2-12 and Pakosie, 2002:121-131).

The transport of enslaved African people from a depot in Africa to their destination – sometimes directly to the plantations concerned, sometimes first to the central depot in Curaçao, an island in the Atlantic Ocean – also took several weeks or even months. The transfer of enslaved African people from Curaçao to the plantations of their new slavers also took weeks or even months. It is clear that during these voyages and on the plantations themselves, new languages emerged to enable communication between people. These languages were composed of words from European languages, the mother tongues of various African ethnic groups, AFRO-AFRICAN and AFRO-EUROPEAN (Euro-African).

After being placed definitively on the respective slave plantations, other new languages will be originated if there is a new Babylonian confusion of speech among the majority of the enslaved African people on the same plantation.

4. LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT AMONG THE MAROONS OF SURINAME

After the forming of Maroon groups in the tropical rainforests of Suriname and French Guiana, the process of language development was continued. This is because the formed new societies consisted not only of people of different African ethnicities but, significantly, also of people from different types of Surinamese slave plantation, and slave plantation experiences. The new originated languages were formed by words from the different languages they already knew, added by words from the languages or dialects that were spoken by the owners of the respective slave plantations where each of the group came from (Pakosie, 2000-2:3-4 and Pakosie, 2002:125-126).

This means that words from the old languages which could no longer be used, disappeared and new one came in their place. It shows us that after the ancestors were forced to leave their native languages for a new language, they developed many languages before the present-day Maroon native languages such as Ndyuka, Saamaka, Pamaka, Matawai, Aluku and Kwiïnti.

Among the languages the Maroons distinguish, which lie in between their original African native languages and their current languages, are Loangu, Kumanti, Papa, Ampuku, Amanfu, Anklibenda and Akoopina. Nowadays these languages are only used in religious ceremonies.

As mentioned, in any of the present-day Maroon languages you will find a number of words from many European languages, such as English, Portuguese, French and Dutch. But English and Portuguese have more affected the present-day Maroon languages. That is why we may divide the six present-day Maroon languages into two main groups:

- Surinamese Afro-English: Ndyuka, Pamaka, Aluku, Kwiïnti and

- Surinamese Afro-Portuguese: Saamaka and Matawai

It may be clear that since the Aluku Maroons are French citizens, their native language is also strong affected by the French language. The same happened with many Dutch words, which you will find in the other Maroon languages, used by the youth of these Maroon groups.

5. WRITING IN NDYUKA-TONGO

Although the Ndyuka Maroon da ATUMISI AFÁKA developed a script for the Ndyuka language at the beginning of the 20th century, until the last three decades the Maroon communities essentially had no written culture and therefore no written tradition.

In the past, even SRANAN TONGO was not regularly used for written communication, except for church translations. Moreover, until the mid‑1980s, no official orthography existed for Sranan tongo, which meant that individuals wrote the language according to their own preferences. Minister ALAN LI FO SJOE of Education, Science and Culture (1984–1988) changed this by appointing a committee of linguists to establish an official spelling system. Nevertheless, many people still write Sranan tongo in their own way. And because no official orthography exists for the NDYUKA language either, we face the same problem. To address this, one must first learn how NDYUKA TONGO is correctly written. Knowledge of the NDYUKA ALPHABET is therefore essential.

6. THE NDYUKA ALPHABET

These are the letters or alphabet to may write in Ndyuka-tongo in the right way.

Vowels: A, E, I,O,U.

The following letter are also to be used: Á, À, É,È, Í, Ì, Ó,Ò,Ú,Ù, Ü.

Consonants: B,D,F,G,H,K,L,M,N,P,S,T,U, (V), W,Y,Z.

A vowel is a letter or symbol that is used to represent a vowel sound in writing. Consonants are letters or symbols that can be used in combination with vowels to form words.

How to use vowels in Ndyuka-tongo:

a like in ana or alisi

e like in eke or ete

i like in ini or ipi

o like in opu or osu

u like in buku or bun

To write Ndyuka-tongo these letters are also to be used:

á like in ná or Abáan

é like in feefeé or geénge

í like in kiní or guligulí

ó like in kódo or bokó

ú like in fúndu

In Ndyuka-tongo you may also use double vowels:

aa like in taa or faan

ee like in beeï

ii like in fii

oo like in boofo or botoo

uu like in buguu or buuse

Sometimes you also have to combine consonants to make a letter to form a word. For example:

dy like in dyalusu or dyebiï

ny like in nyan or nyoni

ty like in tyapoba or tyatyali

Mm like in mma

Except words that are borrowed from another language, there are no words in Ndyuka-tongo that can be written with the letters C,J,Q and X. For the letter V, an investigation is still being conducted into how many Ndyuka words can be written with this letter, in order to determine whether its inclusion is warranted.

Writing in Ndyuka-tongo and speaking Ndyuka-tongo are two different things. The correct way to write Ndyuka-tongo, is to write the words as they are spoken in their full form. For example, if you say: y’ á mu taigi en taki m’ be kon ya, then you should write it as: Yu á mu taigi en taki mi be kon ya.

For a legible and understandable text, you also have to put the correct diacritical marks such as an ‘accent aigu’ on the right vowel or consonant. For example writing or saying: na en or ná en, have two different meanings. Na en is an affirmative, it means, that is it. But ná en, is a negative, and means, that isn’t it. Mma is Mrs, the title used for adult women. But if you say or write Ḿma, it means your mother.

This is equal for writing or saying: sama or sáma? If you write or say Sama, you mean, people in general, for example, den sama fu Soolan (the people of Saint Laurent ). But writing or saying: sáma?, is a question to know who this person is.

In Ndyuka-tongo, words typically end in A, E, I, O, or U. In other words, the final letter of a Ndyuka word is generally a vowel.

There is also a hypothesis that Ndyuka-tongo don’t have the letters H and Z. But looking at the words: hou, hinsii, ho, he, azeman, ze, zekanti, it is clear that these two letters are also part of the Ndyuka alphabet. As I mentioned, the number of Ndyuka words that can be written with the letter V is still being investigated in order to determine whether its inclusion is justified.

In contrast to the African and West-European languages, from which it is derived, Ndyuka-tongo does not have the letter R. Were the R has been dropped from the original word, it is replaced either by a compensatory lengthening of the associated vowel. For example, boofo instead of the Akan (African) word brofo from which it is derived.

But not only the R change into a vowel: a, e, o, i or u, also an intervocalic D in a word will change in Ndyuka into a L. For example, the Sranan-tongo word, ‘brede’, which is derived from the English word bread, is in Ndyuka-tongo, ‘beële’.

7. IDEOPHONES

A common similarity of the Maroon languages, and as far as I know, also of the Black-African languages in Africa , is that they have several ideophones. These are words that are used to distinguish meanings, sounds, colors, movements, emotions and other physical characteristics.

For example:

Writing or saying: A kaba kellé or A kaba kelékelé, describes how someone is all ready.

A kaba gbólon, describes the way it is all gone or it is over.

Some other ideophones are:

Bodoo (grade of softness, limpness)

Píí (quiet, calm, grade of blackness or darkness)

Biogóo (grade of blackness or darkness)

Tóin (grade of small)

Títitíí (grade of small)

Yuwiï (grade of coldness)

Faan (grade of whiteness)

Nyáán (grade of redness or shines)

Dududuu (grade of swollen)

Buwabuwa (grade of heavy steps)

8. MODERN-DAY NDYUKA LANGUAGE

A language is not static; it is liable to the changes of the community who uses it. The rapidity of the changing of a language depends on the fastness of the social changing of the community.

Looking at the Maroon languages, we have seen that from the beginning until now, they are liable to changes. Sometimes the change goes fast, sometimes slowly. For example, the Ndyuka-tongo has made a big change in the last 30 years, especially the last 15 years.

A change in a language not only concerns the new words adopted from other languages which replace old words, but also the fact that a set of customs and rules for polite behaviour get lost in the language.

The present ways of greeting in the Maroon societies, for example has changed a lot in the last 40 years. Until forty years ago, there were still two main forms of greeting, namely an informal form and a formal form. The respectable or formal form was used for greeting respectable persons such as father- and mother-in-law, son-and daughter-in-law, elders and strangers.

To greet a respectable person, you should first take the right attitude, putting your one hand in the other, and than greet. After that you should wait until your greeting was answered completely before you will ask permission to continuing your way. The following example is a demonstration of a respectable form of greeting used in the past in the morning between a man (in this case a pai, son-in-law) and his mai, mother-in-law.

Pai: A kiïn un baka oo mma Pai: Mrs. a new day has come

Mai: A kiïn un baka ye baa Mai: A new day has come indeed

Pai: U doo en Pai: Have you reached it well?

Mai: U doo en baa, u seefi doo en? Mai: We have reached it very well, you too?

Pai: U doo en so mooi ye Pai: Yes, we too have reached it very well

Mai: Ai baa, den taa sama doo en mooi tu? Mai: That is fine, have the others reached it too?

Pai: Den doo en wanes-wanse baa Pai: They have reached it all very well

Mai: Ai baa Mai: That is fine

Pai: A dda doo en mooi tu? Pai: My father-in-law, has he too reached it well?

Mai: A doo en so mooi ye, ma a komoto ya Mai: He woke up in good condition, but

subsequently went somewhere.

Pai: Ai baa. We mma da u o gi piimisi baka Pai: Well mrs. I request permission to leave.

Mai: Ai baa, da u poti daa fosi Mai: That is good, thanks a lot

Pai: A ná a daa baa mma. Pai: You are welcome.

Nowadays, you suddenly hear a voice of someone who says: Fa! (How are you)’. And before you turn to see the person who is greeting you, he disappears. The respectful form of greeting has lost.

As mentioned before changes in a language concern also new words adopted from others. The present generation Maroons dwelling in the whole world, includes many strange words in their Maroon languages. Things are no longer called by the traditional names. For instance where someone of the old generation Maroons would say: mi boliman (the one who takes care of my food, meaning my wife), because according to tradition it is impolite to speak about ‘my wife’ in the presence of elders, one of the present generation would just say: ‘mi uman’, my wife.

Some expression also lost their values, because of the changes in the societies. In former days a woman could say: ’that person is my ‘kiiman’ (killingman) or my ‘goniman‘ (gunman, the one who bears the gun), and everyone would know that she means, her husband, the man who bears the gun to kill the meat for her to cook. This is because in the past time a man would not bear the gun if he wasn’t going hunting. People would also not use a gun to kill another human being. But things are changes now, if a woman would remark her husband as ‘kiiman‘, it could also be taken literally, since a gun is no longer used only to hunt but also as a weapon to murder.

9. TWO CONCLUDING REMARKS

9.1. On the Complexity of Ndyuka and other Maroon languages

Even as in Aluku and Pamaka, for instance, there is a variant called ‘Nengee’. The term Nengee in linguistic sense is not the same as what is called Nengee-tongo. The term Nengee-tongo is used to indicate the Maroon languages (and Sranan-tongo). But Nengee in linguistic sense is a variant in Ndyuka, Aluku and Pamaka (and as far as I know, also in Saamaka), which is sometimes very difficult to understand if you don’t have knowledge of the language. One may say in Nengee to you: ‘yu a si a de a pe, nyan ala!’ (There is it, eat it all!). In Nengee, this does not imply that one is permitted to eat everything to which the expression refers. Rather, it serves as a warning not to eat all of it, or even to refrain from eating the food altogether.

If one means that you may eat all, he would said: ‘a sani di de ape yu sa nyan ala o’ (do you see that thing over there, you may eat it all).

9.2. On the Classification of the Maroon Languages

As I mentioned before, the Maroon languages can be divided into two main groups:

- SURINAMESE AFRO-ENGLISH: Ndyuka, Pamaka, Aluku and Kwiïnti; and

- SURINAMESE AFRO-PORTUGUESE: Saamaka and Matawai.

The fact that some of the languages, for example, Ndyuka, Pamaka, Aluku and Kwiïnti are classified in the same group, don’t mean that these four languages are the same. They may have common words with the same meaning, but they also have common words but with different meaning. The Aluku word kali (“to call”) means “to propel a boat” in the variety of Ndyuka spoken by the Okanisi Maroons of the Upper Area. In both Aluku and Pamaka, the word weli means “to get dressed”. In the Ndyuka of the Upper Area, however, weli means “tired” or “weary”. The Ndyuka term used in the Upper Area for “to get dressed” is wei, which is also the term for “to engage in prostitution”. In Pamaka and Aluku, wei exclusively means “to engage in prostitution”.

10. BIBLIOGRAPHY

Pakosie, André R.M., Een etymologische zoektocht naar Afrikaanse woorden in de 2000 Ndyuka taal. In: Siboga jrg. 10 nr. 2.

Pakosie, André R.M., Akan heritage in Maroon culture in Suriname. In: I. Van Kessel 2002 (ed.) Merchants, Missionaries & Migrants, 300 years of Dutch- Ghanian relations. KIT Publishers, Amsterdam .

[1] Andre R.M. Pakosie. Born in 1955 in Diitabiki in the Tapanahoni region (interior of Suriname). Naturopath, phytotherapist (according to the tradition of the Maroons from the tropical rainforest of Suriname), Maroon historian, writer, poet, editor-in-chief of Siboga (the magazine for Maroon culture and history), chairman of the Maroon Institute Foundation Sabanapeti, Documentary filmmaker, Kabiten (traditional leader) of the Okanisi Maroons in the Netherlands from 2000-2012, Edebukuman (head and guardian of the Afáka syllabic script) since 1993, founder (1974) of the Dag van de Marrons. Bearer and guardian of the highest Maroon award, the Gaanman Gazon Matodja Award, Ridder in de Ere orde van de Gele Ster (Knight of the Order of the Yellow Star), Suriname. Made his debut as a writer in 1972 at the age of 17 with the book: De dood van Boni. Writes prose and poetry. Besides his own publications, he has also published in renowned journals such as ‘The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law’ (University of Birmingham, England), De Gids, NWIG (New West Indian Guide/New West Indian Guide), OSO (Journal of Surinamese Linguistics, Literature and History) and BSS (Sources for the Study of Suriname). Specialises in Maroon culture and history.

[1] Andre R.M. Pakosie. Born in 1955 in Diitabiki in the Tapanahoni region (interior of Suriname). Naturopath, phytotherapist (according to the tradition of the Maroons from the tropical rainforest of Suriname), Maroon historian, writer, poet, editor-in-chief of Siboga (the magazine for Maroon culture and history), chairman of the Maroon Institute Foundation Sabanapeti, Documentary filmmaker, Kabiten (traditional leader) of the Okanisi Maroons in the Netherlands from 2000-2012, Edebukuman (head and guardian of the Afáka syllabic script) since 1993, founder (1974) of the Dag van de Marrons. Bearer and guardian of the highest Maroon award, the Gaanman Gazon Matodja Award, Ridder in de Ere orde van de Gele Ster (Knight of the Order of the Yellow Star), Suriname. Made his debut as a writer in 1972 at the age of 17 with the book: De dood van Boni. Writes prose and poetry. Besides his own publications, he has also published in renowned journals such as ‘The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law’ (University of Birmingham, England), De Gids, NWIG (New West Indian Guide/New West Indian Guide), OSO (Journal of Surinamese Linguistics, Literature and History) and BSS (Sources for the Study of Suriname). Specialises in Maroon culture and history.

THE MAROON TRADITIONAL AUTHORITY AT THE CROSSROADS OF TRADITION AND MODERNITY

By: Andre R.M. Pakosie[1]

COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This article was previously published by me in the Maroon journal SIBOGA, Volume 17, No. 2, 2007. All my articles are protected by copyright. No article written by me may be reproduced or published, in whole or in part, in any form whatsoever without proper source citation.

The content of this article is based on the introductory address I delivered, as the founder of the Day of the Maroons, on 6 October 2007 during the 33rd celebration of the Day of the Maroons in the Netherlands (Rotterdam).

1. Introduction

I have titled this article “The Maroon Traditional Authority at the Crossroads of Tradition and Modernity.” This title reflects the current position of the Maroon traditional authority: an institution balancing between past and present, seeking an appropriate path within the new era into which Maroon communities have entered. The direction chosen will be decisive for the future survival and functioning of the traditional authority. For this reason, it is essential to stimulate a broad discussion on the matter. This article aims to contribute to that debate.

The article first outlines several key aspects intended to provide the reader with insight into the social and political organisation of traditional Maroon society, including its matrilineal structure, administrative responsibilities, judicial practices, and the evolution of traditional authority over the centuries. Through case studies, the article then illustrates the efforts of the central government in Paramaribo, from the colonial period onward, to undermine the traditional authority. The political reluctance of the Surinamese government to develop the Interior is unmistakably evident in this context. Finally, I offer several recommendations for safeguarding the traditional authority and for enhancing its potential to contribute positively to the future development of Surinamese Maroon communities.

A preliminary remark. When describing aspects of Maroon societies, it is important to recognise that many concepts cannot be translated directly without losing essential meaning. Anthropologists in particular tend to translate words, terminology, and titles from the languages of the communities they study into their own languages. This often results in distortions and misinterpretations.

The use of the term “tribe” for communities in non‑Western societies, such as those of the Maroons, is entirely inappropriate. In the case of Maroon societies, one should employ the terminology used by the Maroons themselves, namely Gaán-lo or Nási. A Gaán-lo or Nási refers to a Maroon ethnic community.

Terms such as paramount chief and captain are likewise inappropriate and do not reflect the meaning or function of the titles used in the Maroon languages, namely Gaanman and Kabiten. A Gaanman is the highest leader, or, as elders used to say, the King of a Maroon ethnic community. A Kabiten is the leader of a Lo (a sub‑Maroon ethnic community) and/or of groups of people who, whether or not belonging to the same Lo, reside together outside their traditional territory.

2. Maroon societies in Suriname, French Guiana, and the diaspora

At first glance, Maroon societies may appear simple, but in reality they are highly complex. Understanding their basic structure is therefore essential for grasping this complexity.

There are five Maroon ethnic communities whose traditional territories lie in the interior of Suriname, and one Maroon ethnic community whose traditional territory lies in French Guiana. These six Maroon communities, Gaán-lo or Nási, are:

- Ndyuka or Okanisi, whose traditional territories lie along the Tapanahoni, Saakiiki, Cottica, Commewijne, Saramacca River (Santigoön and Totikampu), and Fuüduïni (lower Marowijne River: Bilokondeë to Pakila);

- Saamaka, with traditional territories along the Pikinlio, Gaanlio, and both above and below the reservoir;

- Pamaka, whose traditional territory lies along the Marowijne River between Tapudan and Bofootabiki;

- Matawai, with traditional territory along the Matawailiba (upper Saramacca River);

- Kwiïnti, with traditional territory along the Coppename River;

- Aluku or Boni, whose traditional territory lies in French Guiana (the Lawa and the lower Marowijne River).

Nowadays, people also talk about Surinamese and French Guianese Maroons in the diaspora because members of the six Maroon ethnic groups are scattered across the globe. When Maroons live outside their traditional homelands and integrate into different societies, certain aspects of their ethnic identity change, such as their food, clothing, music, religion, values and norms. In the diaspora, Maroon children often develop a different ethnic identity to that of their parents.

The farther and more isolated Maroons live from their traditional societies, the more easily they may lose their language, values, and norms. These are, to varying degrees, replaced by those of the new society in which they reside.

In contexts where Maroons settle in concentrated numbers, particularly when they originate from the same ethnic community, they make considerable efforts to preserve their traditions. They often establish cultural or advocacy organisations. Nevertheless, such initiatives cannot fully halt the processes of change.

3. Matrilineal organisation, authority structure, and social order

Each Gaán-lo is headed by a Gaanman. Since the second half of the eighteenth century, Maroon communities have maintained a clear and significant societal structure consisting of a political‑administrative order, regulating governance, justice, and religious affairs, and a socio‑cultural order, which is primarily based on a matrilineal kinship system.

This matrilineal system means that children are affiliated with the maternal lineage, and that the succession to positions of authority likewise follows this line. The authority structure consists of the various matrilineal segments that constitute the society: Osu, Mamapikin, Beë, and Gaán-lo or Nási.

3.1. Osu

The Osu is the household unit and consists of the mother and her children, who belong to the same matriline, and the man, the father of the children, who belongs to a different matriline. As long as he resides with the mother of his children, he is considered part of the Osu of his wife.

Authority within the Osu rests secondarily with the parents but primarily with the mother’s matrilineal brothers and sisters, the children’s Tiyu and Tiya. Terms such as uncle, aunt, brother, and sister carry different meanings in Maroon societies. Cousins on both the maternal and paternal sides are also regarded as uncles and aunts, because the terms brother and sister also apply to cousins.

According to Maroon customary law, matrilineal uncles and aunts are legally considered the ‘father’ and ‘mother’ of the children of their matrilineal sisters. They are responsible for ensuring that these children are raised properly. The heads of the household, the mother and the father, are therefore accountable to the matrilineal uncles and aunts of the mother for the functioning of their family unit.

3.2. Mamapikin

A Mamapikin is a matrilineal segment composed of individuals who share a common grandmother and/or great‑grandmother. It consists of several Osu together, excluding the fathers within the Osu, as they belong to different matrilines. Authority within this segment rests with the matrilineal uncles and aunts.

3.3. Beë

The Beë is the matriline. It is formed by several Mamapikin who share the same Gaánḿmafubeë: the woman who was brought from Africa to Suriname during slavery and from whom the group descends. The Beë therefore provides the most valuable information for tracing the African origins of Maroon groups.

The Gaántiï and Gaántiya (grand‑uncles and grand‑aunts) of the members of the Mamapikin constitute the authority of the Beë. They are the matrilineal brothers and sisters of the grandmother. The Kabiten, the highest authority within a Lo, is selected from a Beë.

3.4. Lo

A Lo is a matrilineally structured sub‑ethnic group, generally composed of several Beë that do not necessarily share blood ties. Authority within the Lo is exercised by the Kabiten, who is assisted by his Basiya. The grand‑uncles and grand‑aunts within the Beë are accountable to the Kabiten.

3.5. Gaán-lo or Nási

The Gaán-lo or Nási constitutes the entire matrilineally structured ethnic community. It is composed of several Lo, with a Gaanman as the highest leader. In some Maroon societies, the Gaanman is also, sometimes only nominally, the highest spiritual leader of his people.

A Maroon authority figure thus serves as an intermediary between the living, the dead, and the divine.

4. Inheritance, norms, and values

In traditional Maroon societies, the question of who should assume the authority of Kabiten or Gaanman is entirely determined by the matrilineal structure. The Maroon inheritance system ensures the continuity of both material and immaterial heritage, passed down through the maternal line for generations. The Maroon family bond is elastic and virtually limitless. As a result, each Maroon has a large number of potential heirs: from the children of mothers and maternal aunts to their grandchildren and great‑grandchildren, an inheritance system that traces back to the Gaánḿmafubeë.

A core norm in traditional Maroon societies is that a person must have respect for themselves, and therefore also for others and for their surroundings. This principle forms the foundation of upbringing and social formation and is deeply embedded in the authority and social structures. The educational system is designed to prepare every Maroon child for a potential leadership role. In principle, any Maroon can become a leader. They live not only for themselves but for the community as a whole.

There is a strong sense of collective responsibility. Those who fail to adhere to prevailing norms and values are regarded as wisiwasiman, a useless person, a label no one wishes to bear.

Maroon societies have traditionally been governed on the basis of authority. Authority can only be earned through ethical conduct, respectable qualities, and functional contributions to the community. In the traditional legal system, weapons and prisons are generally unnecessary to maintain order.

5. Administrative responsibility in traditional Maroon society

Each Maroon society, the Gaán-lo or Nási, is governed by the Lanti-fu-a-Liba, the council responsible for the traditional territory. This governing body consists of the college of Kabiten and Basiya, assisted by the Bendi-a-se-man, an advisory popular council whose composition may change over time. The Gaanman is ex officio the head of the Lanti-fu-a-Liba and is considered inviolable.

The Lo-lanti, composed of the Kabiten and Basiya of the Lo and supported by a village council with a similarly variable composition, forms the governing body of a Lo. The Lo-lanti is accountable to the Lanti-fu-a-Liba.

The Lanti-fu-a-Liba meets at least once a year and is chaired by or on behalf of the Gaanman. This meeting is called Twalufu-Lo-kuütu or Liba-kuütu. During this assembly, future policy is discussed and laws are created or amended. A new law becomes effective only after it has been ratified by the Gaanman. It should be noted that the Gaanman, although he is the highest leader, is not authorized under Maroon customary law to implement major changes without the prior approval of the Lanti‑fu‑a‑Liba.

The Maroon governance system employs a highly developed form of decision‑making. Decisions are not made by majority vote; members do not vote for or against proposals. Instead, decisions are reached through consensus. Discussion continues until full agreement is achieved. A decision must have the approval of all participants present. No one may leave the meeting with a deeply unsatisfied feeling about the outcome.

6. Judicial system

In each segment of Maroon society, one or more individuals hold authority. These individuals are addressed when a member of their segment commits an offense. Judicial proceedings and all other lawful actions are carried out in the name of the Gaanman and the Lanti.

Depending on the nature and severity of the offense, judicial proceedings take place at the level of the various segments: Osu, Mamapikin, Beë, Lo, or Nási. In cases of serious offenses that affect the entire community, justice is administered at the Nási level. The Gaanman and the Lanti then hold the Kabiten of the offender responsible for the wrongdoing of his subordinate. The Kabiten may even receive a substantial fine.

The Kabiten then brings the imposed penalty to his Lo and holds the authority of the offender’s Beë responsible, imposing the penalty on him. The Beë authority then holds the authority of the offender’s Mamapikin responsible, who in turn addresses the Osu and the offender directly and ensures that the punishment is carried out.

This system implies that when an individual commits a wrongful act, the entire structure, Lo, Beë, Mamapikin, and Osu, is held responsible. This reflects a principle of collective responsibility. Maroon societies also maintain strong social control: community members monitor one another closely. As a result of this social regulation and the effectiveness of the judicial process, relatively few offenses occurred in the past, and virtually no one escaped punishment.

7. The evolution of traditional Maroon authority

The various leadership positions are, as noted earlier, hereditary. However, in early Maroon history this was not the case. During the Lowéten, the period between fleeing the plantations and establishing permanent settlements, each Lo selected its own leader, a person with proven leadership qualities. This meant that in a territory with, for example, twelve Lo, twelve equal leaders operated simultaneously, which was not conducive to unity.

Thus, once several Lo had united to form a single ethnic community, the Nási or Gaán-lo, one leader from among all the Lo leaders was appointed as primus inter pares, the first among equals, bearing the title Gaanman.

Over time, however, the Gaanman can no longer be regarded as primus inter pares, because within his own Gaán-lo or Nási he has no equals. His only equals are the Gaanman of the other Maroon communities. Within his own community, the Gaanman is the supreme leader.

7.1. Autonomy

For centuries, Maroon authority figures operated entirely independently and exercised their leadership without external interference. When the colonial government entered into negotiations with them regarding peace, both parties did so on the basis of mutual autonomy and a certain degree of equality. Nevertheless, it must be noted that the peace treaties also negatively affected traditional Maroon authority.

The colonial authorities effectively purchased, in a psychological sense, the autonomy of Maroon traditional leadership. When the peace treaties were concluded, the colonial government committed itself to sending annual ‘gifts’ to the Maroons. The Maroons specifically requested items they urgently needed, such as firearms, gunpowder, lead, machetes, and axes. However, the colonial administration sent these essential goods only in limited quantities, while providing ample supplies of hats, mirrors, and other items of little practical value. Through psychological manipulation, the colonial authorities ultimately succeeded in creating a perceived need for these items among the Maroons.

Once the colonial authorities observed that the Maroons had become fully dependent on these goods, they decided in 1857 to discontinue the shipments. In their place, they introduced an annual allowance of three hundred guilders, twenty‑five guilders per month, exclusively for the Gaanman. This amount could be increased if the Gaanman, and thus the traditional leadership, demonstrated willingness to act in accordance with the government’s expectations. In other words, if the traditional authority made itself subordinate to the colonial administration in Paramaribo.

8. Attempts to Undermine Traditional Maroon Authority

Since the signing of the peace treaties in the 1760s, it has been customary for the Gaanman, once enthroned by the Maroon communities, to travel to Paramaribo for recognition by the colonial government, the bakaä‑lanti.

Over time, the political authorities in Paramaribo began to interpret this act of recognition, partly because the Gaanman and later also the Kabiten and Basiya began receiving state allowances, as a formal “swearing‑in” of the Gaanman. During the colonial period, an oath formula was read to the Gaanman as part of the recognition procedure, instructing him on what he was required to do. In doing so, he swore allegiance to the Dutch crown. After Suriname’s independence, this practice was continued by the Surinamese government, requiring the Gaanman to swear an oath of loyalty to the president.

As a result, a Gaanman is effectively subjected to two separate oath rituals. Upon his installation by his own people, he has already taken a solemn oath through ceremonies conducted on both the human and spiritual levels. For his recognition by the state, he must then take a second oath, this time grounded in Western legal and political norms.

This colonial legacy need not have persisted in independent Suriname, had those in positions of political authority taken the time to understand the traditions of the Maroon and Indigenous communities, traditions that are not rooted in Western concepts of legitimacy and governance.

The authority figures in the interior, who had previously been entirely autonomous and effectively constituted a separate polity, were thereby rendered subordinate to the political power in Paramaribo.

From the colonial period onward, numerous attempts were made to impose administrative structures on Maroon societies or to appoint individuals favored by the government to positions of authority. In doing so, the traditional leadership was systematically undermined. The historical cases illustrate:

- the various attempts by the government to weaken traditional Maroon authority;

- the difficult position in which a Gaanman may be placed when national political power interferes with traditional authority without regard for the cultural‑religious foundations upon which that authority rests;

- that it is not the traditional leadership structures that hinder development in the interior, as is often claimed, but rather the political unwillingness of Paramaribo.

9. Case 1. Fabi Labi versus Pamu Langabaiba

Between 1760 and 1764, following the peace agreement, the colonial government attempted, unsuccessfully, to remove gaanman Fabi Labi of the Dikan-lo and replace him with Pamu Langabaiba of the Otoö-lo. These attempts are clearly reflected in colonial propagandistic writings.

Louis Nepveu wrote in his Journal of 1762, two years after the peace with the Okanisi Maroons, that during his visit to the Okanisi, aimed at negotiating peace with the Saamaka Maroons, it appeared that Labi had been deposed in April 1762 in favor of Pamu. He further claimed that Pamu would be removed if he failed to govern properly (Scholtens 1994:164; De Beet & Price 1982:137–139; De Groot 1969:14).

The Journal of Vieira and Collerius (7 November – 2 December 1760) likewise refers to “Pamu, who was then known as the successor of Labi” (ARA‑1, OAS, RvP, inv.nr. . 62).

However, as Pakosie (1999:29) notes, “no Okanisi historian is aware of any instance in which Gaanman Labi was deposed, as the archival documents suggest.”

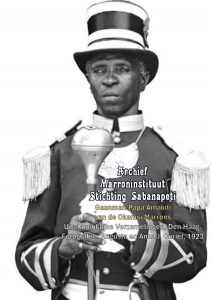

10. Case 2. Papa Amakiti versus Yensa Kanapé

In the early twentieth century, the colonial government attempted to depose gaanman Papa Amakiti and appoint his nephew Yensa Kanapé as Gaanman. This effort failed because the people continued to support Amakiti.

The colonial administration nevertheless made Amakiti’s life difficult. Upon his recognition by the colonial authorities, his allowance was set at only 500 guilders per year, half that of his predecessor Oseïse. A celebratory event planned by the Okanisi Maroons in Albina to welcome the new Gaanman was prohibited by District Commissioner S.E. Juta (Scholtens 1994:75).

In his correspondence, Juta described Amakiti in extremely negative terms, calling him “a person of no consequence” and “mentally and physically demoralized” (Scholtens 1994:75; Pakosie 1999:67).

Postholder Willem van Lier likewise claimed that Amakiti lacked influence and was incapable of governing the Okanisi Maroons, while Kanapé was, in his view, the appropriate leader. These claims were unfounded: Amakiti did possess authority. His nickname Amakiti derived from the statement of his followers: “Gaanman Papa baa, gaanman a makiti”, “Gaanman Papa, the Gaanman has power” (Pakosie 1999:67).

The colonial government subsequently appointed Kanapé to a newly created position of ‘groot-kapitein’ and placed him alongside Amakiti as a parallel authority. The administration dealt exclusively with Kanapé.

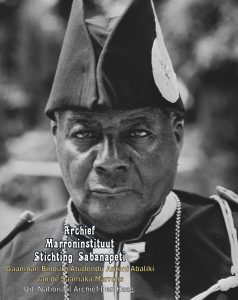

11. Case 3. Gazon Matodja versus Pengel and Asenfu

In 1964, the then Gaanman of the Okanisi, Akontu Velantie, passed away. In accordance with tradition, a twelve‑month mourning period was observed. During this period, a notable is appointed to act as interim Gaanman. Discussions regarding succession do not take place publicly; they occur exclusively behind the scenes.

It is even taboo to speak about the rightful successor during the mourning period. At the end of this period, all authority figures gather at the Gaanman’s residence for the Boökode, the closing ceremony of mourning. This ceremony lasts one week, and even then the topic of succession remains taboo.

After the Boökode, the notables return to their respective villages. A period of at least three months is then observed before a committee of authority figures, Kabiten, Basiya, and Obiyaman, grants the acting Gaanman permission to convene a Liba‑kuütu (popular assembly), during which the new Gaanman will be enthroned.

The village leaders who participate in the Liba‑kuütu are informed of the date and simultaneously receive the official announcement of the name of the new Gaanman.

The enthronement of the Okanisi Gaanman does not take place at the residence in Diitabiki, but in the village of Puketi, the Edekondeë (capital) of the Okanisi Maroon society.

From the death of a Gaanman until the coronation of his successor, the Okanisi Maroons of that period strictly adhered to the prescriptions of the Sweli Gadu, the highest oracle of the community. No dignitary would act independently during this transitional phase. If anything were to befall the new Gaanman, for example, if he were to remain in office only briefly, this would be attributed to a failure to observe the ancestral and religious rules. It would then be assumed that the new Gaanman had not received the blessing of the gods, the ancestors, and in particular his deceased predecessor. According to Okanisi Maroon tradition, the spirit of the deceased Gaanman continues to rule throughout the entire tenure of his successor. Consequently, in all major decisions concerning the coronation of a new Gaanman, the directives of the predecessor’s spirit were decisive.

Regarding the conflict surrounding the succession of gaanman Akontu Velantie, the following applies. When the Okanisi Maroons in 1965 were preparing the ceremonies marking the end of the official mourning period, the Surinamese prime minister at the time, Johan Adolf Pengel, decided to travel to Diitabiki with a large delegation of national and international guests. The purpose of this visit was to install the new Gaanman of the Okanisi Maroons. In doing so, Pengel acted in violation of both the rules of the Okanisi community and those of the central government. Only the Okanisi Maroon people are authorized to crown their own Gaanman, and only the governor — then the representative of the Dutch Crown — was authorized to subsequently recognise him. Pengel’s intervention caused great unrest and disrupted Okanisi Maroon society.

For the intended new Gaanman, da Gazon Matodja, this created a serious dilemma. Recognition by Paramaribo was necessary, as otherwise the allowances and other privileges granted by the government to traditional authorities could be withdrawn. Moreover, without the support of the bakaä‑lanti (the government in Paramaribo), the anticipated development according to Western models, initiated during the final year of gaanman Akontu Velantie’s leadership, could not have continued in the traditional territory of the Okanisi Maroons.

This development included:

- the installation in 1964 of a power generator in the Gaanman’s village, providing electricity for the first time, albeit only from 6:00 p.m. to 9:30 p.m. and dependent on the availability of fuel;

- the construction of a school with boarding facilities across from Diitabiki; although the school opened, the boarding facility never did and was left to deteriorate by the government;

- the establishment of a medical post by the Evangelical Brethren Church (EBG).

Although da Gazon Matodja, as Gaanman, required the support of Paramaribo, he could not, as a member of the Okanisi Maroon community — and especially as the future Benpenimaunsu, representative of the supreme deity, the gods, and the ancestral spirits — violate the laws of his people, which are grounded in the covenant between the ancestors and the gods. For him, it was therefore preferable to risk human punishment rather than incur the wrath of the invisible powers. He refused to be crowned by Prime Minister Pengel in violation of tradition.

Notably, the Dutch historian Dr. Silvia W. de Groot, who was among Pengel’s foreign guests, had warned him beforehand that he needed to respect the decision of the Sweli Gadu if his mission were to succeed. Pengel reportedly replied mockingly: “I am more powerful than their god.”

After several unsuccessful attempts to meet with da Gazon Matodja, Pengel finally succeeded. When Matodja asked him the reason for his visit, Pengel replied: “I have come to Diitabiki to install Mr. Gazon as Gaanman.” He addressed Matodja in Dutch — a language he did not understand — even though Pengel normally spoke Sranantongo, the lingua franca that Matodja did understand. Da Gazon Matodja responded: “Among the Okanisi there are three to four individuals named Gazon. I am the Gazon of Diitabiki. If I am the one you seek to crown as Gaanman, I can tell you that as long as the closing ceremonies of the mourning period for my uncle, the late Gaanman Akontu Velantie, have not been completed according to the prescribed rules, I will allow no one to crown me as Gaanman” (Pakosie 1999:111).

Pengel returned to Paramaribo empty-handed. He had to learn that political power has no effect among the Okanisi Maroons when it conflicts with the rules of their ancestors and their religion.

Only months after the Boökode was da Gazon Matodja, in 1966, crowned Gaanman in Puketi according to customary procedures. Later that year, he travelled to Paramaribo for official recognition by the bakaä‑lanti. A cordial relationship between Pengel and da Gazon Matodja never developed. Johan Adolf Pengel died in 1970.

Because Pengel, unlike with gaanman Akontu Velantie, did not enjoy a friendly relationship with gaanman Gazon Matodja, his political party, the N.P.S., encouraged gaanman Akontu Velantie’s younger brother, da Asenfu, an uncle of gaanman Gazon Matodja, to undermine the authority of the Gaanman. The N.P.S. informally appointed da Asenfu as “prime minister” of the Okanisi Maroons, parallel to the Gaanman. He received the same privileges: a service boat, an outboard motor, boatmen, and government‑funded accommodation in Albina and Paramaribo during his visits. As a result, the functioning of gaanman Gazon Matodja was significantly hindered. Ultimately, the Okanisi Maroon community intervened and called da Asenfu to order during a meeting in Diitabiki in December 1969.

12. Case 4. Kofi Gbosuman versus Abraham Wetiwoyo

Among the Saamaka Maroons, the colonial administration deposed gaanman Kofi Gbosuman on 18 February 1835 in favor of his stepson Abraham Wetiwoyo. The reason was that Gbosuman refused to return individuals who, after the peace agreement, had liberated themselves from slavery and joined his community. From the Saamaka Maroon perspective this refusal was justified, but the colonial authorities did not accept it.

Gaanman Agbago Aboikoni told me in conversation that gaanman Abini of the Matyau‑lo married ma Akuumi of the Awana‑lo and fathered seven children with her, among whom was taata Alabi Palantó. In this account, gaanman Agbago Aboikoni diverges from the written historical record. Both Otniel (Ottie) Jozefzoon (1951:15) and Richard Price (1990:413) refer to Alabi Pantó, whereas gaanman Agbago Aboikoni clearly spoke of Alabi Palantó.

After the death of gaanman Abini, the Saamaka Maroons were without a Gaanman for some time. Eventually, the then‑leader of the Nasi‑lo, Kwaku Etya, was appointed as Gaanman, serving from 1775 to 1783 (Scholtens et al., 1992:125). The Nasi‑lo is distinct from the Matyau‑lo.

Following the death of gaanman Kwaku Etya in 1783 (Scholtens et al., 1992:126), Alabi Palantó of the Awana‑lo, son of the former Matyau‑gaanman Abini, became Gaanman of the Saamaka Maroons. Alabi Palantó converted to Christianity and served as Gaanman from 1783 to 1820 (Scholtens et al., 1992:126). His Christian faith within a largely non‑Christian community created tensions. A similar situation occurred in 1895 with the Christian Gaanman of the Matawai, Johannes King, who felt unable to reconcile his Christian identity with the gaanmanship and returned the office to his people in 1896.

After the death of gaanman Alabi Palantó, the spirit of ma Yaya Dandé, niece of taata Lanu and taata Ayako, ensured that the gaanmanship returned to the Matyau‑lo. Mama Yaya Dandé lived from 1684 to 1782 (Price, 1990:10). In 1821, taata Gbagidi Gbago was appointed as Gaanman (Scholtens et al., 1990:126), but he died in the same year, before being officially recognised by the colonial administration. He was succeeded by taata Kofi Bosuman, also known as Kofi Gbosuman, of the Nasi‑lo. Taata Kofi Gbosuman served as Gaanman from 1822 to 1835 (Scholtens et al., 1992:127). He was a grandson of the sister of taata Kwaku Etya, the earlier Nasi‑lo gaanman.

Taata Kofi Gbosuman was married to a woman named ma Yaya from the Matyau‑lo (not to be confused with ma Yaya Dandé), who served as a medium for an important Ampuku deity, Saa. From an earlier marriage between ma Yaya and taata Sabi, a son had been born: Abaän (Abraham) Wetiwoyo. Through her marriage to taata Kofi Gbosuman, he became the stepfather of Abraham Wetiwoyo.

Following the sudden death of gaanman Gbagidi Gbago, there were no adult men within the Matyau‑lo who could assume the gaanmanship. The designated successor was Abraham Wetiwoyo, but he was still too young to hold the office. Ma Yaya therefore played a decisive role in the succession process: she ensured that the gaanmanship passed to her husband, Kofi Gbosuman of the Nasi‑lo. Both ma Yaya, her husband, taata Kofi Gbosuman, and his family had their own interests in this arrangement. Ma Yaya secured her husband’s appointment as Gaanman with the intention that, upon his death, he would be succeeded by her son, Abraham Wetiwoyo, a Matyau, who by then would have reached adulthood.

The family of taata Kofi Gbosuman, the Nasi‑lo, assumed that with his appointment the gaanmanship had permanently returned to their Lo. According to gaanman Agbago Aboikoni, gaanman Kofi Gbosuman was also the first Saamaka Maroon Gaanman to receive a uniform from the colonial administration (interview by Silvia de Groot, 1971; interview by André R.M. Pakosie, 1977).

A tragic event in the career of taata Kofi Gbosuman as gaanman would, however, cause the gaanmanship to return in an unusual way to the Matyau‑lo, in the person of his stepson Abraham Wetiwoyo. Gaanman Kofi Gbosuman rightly refused to surrender enslaved people who had fled the plantations and joined the Saamaka Maroons, despite the stipulations of the 1762 peace treaty. The colonial administration succeeded in rallying a majority of Saamaka Maroon leaders behind its plan and deposed gaanman Kofi Gbosuman. On 18 February 1835 (Oudschans Dentz, 1948:37; Scholtens et al., 1992:166), he was removed from office during a special meeting attended by seventy Saamaka Maroon village leaders and citizens. Three days earlier, on 15 February, the decision had already been made to appoint Abraham Wetiwoyo as his successor (Oudschans Dentz, 1948:37). A year later, in 1836, taata Kofi Gbosuman died.

In the deposition process, his stepson Abraham Wetiwoyo played a particularly reprehensible role (see Oudschans Dentz, 1948:33–43). This ultimately resulted, in accordance with Maroon tradition, in the creation of a Kunu, the Gbosuman-Kunu, within the Matyau‑lo. Kunu is an inherited curse that afflicts a family when a member commits an act (Mekunu) that causes serious harm to another person and ultimately leads to that person’s death (Pakosie, 1991:17). A Kunu follows the matrilineal line of the perpetrator. In this case, the Gbosuman-Kunu affected the maternal line of Abraham Wetiwoyo, the Matyau‑lo. As a result, the Matyau‑lo became dependent on the Nasi‑lo of taata Kofi Gbosuman. According to gaanman Agbago Aboikoni, every new Matyau‑Gaanman must seek reconciliation with the Gbosuman-Kunu through the Nasi‑lo.

With the appointment of Wetiwoyo, the gaanmanship returned to the Matyau‑lo. Wetiwoyo served as Gaanman from 1835 to 1867 (Scholtens et al., 1992:127).

13. Case 5. Muana Dyankuso

Despite three repeated summonses from the political authorities in Paramaribo, the Saamaka Maroon gaanman Muana Dyankuso was unable to travel to Paramaribo in 1924 for consultations. This was due to religious obligations related to the Gbosuman‑Kunu, a curse believed to rest upon his family. For the Maroons, obligations toward the Kunu take precedence over all else. Had gaanman Dyankuso set aside these obligations to comply with the summonses, this would, according to religious belief, have led not only to his own destruction but also to that of his entire family. It was therefore a matter of incapacity, not unwillingness.

Paramaribo, however, refused to acknowledge this and interpreted his absence as a refusal. According to the colonial authorities, gaanman Dyankuso had thereby violated the renewed peace treaty of 1835. As a punitive measure, the government ordered soldiers to block the river providing access to the Saamaka Maroon territory. A representative of the colonial administration, Mr. Junker, even attempted to incite several Kabiten against the Gaanman and to implement a divide‑and‑rule strategy. He wrote: “Only the application of divide and rule would assure me the desired result.”

In March 1924, gaanman Muana Dyankuso finally arrived in Paramaribo, where he was informed that the colonial administration had decided to divide his traditional territory into three parts, thereby restricting his authority. In response, gaanman Dyankuso stated: “We have come here to listen to the laws that the whites make for us, about us, without us.” The colonial authorities were unable to grasp the significance of this criticism.

After Suriname’s independence in 1975, politicians in the national power center continued to appoint individuals as Kabiten and Edekabiten within Maroon societies for partisan reasons, without considering that a person can only be appointed to a position of authority after having earned respect and legitimacy through ethical conduct, personal qualities, and functional contributions within the community. Because these political appointments lack traditional foundations, the individuals concerned often lack genuine authority and respect.

It is evident that externally imposed structures have never functioned effectively within Maroon societies, yet they have contributed to the weakening of traditional leadership roles.

14. The political unwillingness of Paramaribo is the cause of the hindrance to the development of the interior

Traditional authority has still not been constitutionally recognised since 1975. It exists only in a tolerated form, making it vulnerable and easily subject to manipulation.

In 1980, several sergeants led by Dési Bouterse seized political power in Paramaribo through an armed coup. The military regime sought to abolish traditional authority. In 1981, it presented the policy document Towards a New Policy for the Interior. In 1982, this document was included as Annex 1 in the Policy Memorandum of the Ministry of Home Affairs and Justice. It stated, among other things: “The dismantling of existing structures must be pursued gradually, while at the same time modern structures must be introduced with great caution.”

According to the authors of the document, traditional structures hindered the development of the interior and were of interest only to scholars. The document recommended placing the dignitaries of the interior under a foundation. This would, on the one hand, improve the regulation of their legal status and, on the other, allow for a clear definition of their tasks. The Gaanman themselves were to decide whether or not they wished to work within this foundation.

The military regime also attempted to establish so‑called people’s committees and people’s militias in the residential areas of Maroons and Indigenous peoples, parallel power structures alongside the traditional authorities. At a police and fire brigade conference, Ramon de Freitas, who delivered a lecture on “the handling of criminal cases in the interior,” argued that the treaties from which the Maroons derive their autonomy were outdated and obsolete. According to him, these treaties had moreover been concluded unjustly. “The Maroons,” De Freitas claimed, “must, as a result of the February 1980 coup, submit to the new authority (i.e., the military regime AP), an authority that exercises absolute control over the territory of Suriname.”

De Freitas further stated: “A lenient attitude toward law enforcement officers would weaken the authority of Paramaribo (i.e., the military regime) in the interior. Only a firm stance toward these people in their residential areas yields results. For this reason, every residence of a gaanman must have a police and military post.” (Pakosie 1999:145–146).

The policy document in which these ideas were elaborated was never discussed with the traditional authorities themselves. It originated from civil servants in Paramaribo acting on behalf of the military regime. The document amounted to an attempt at the gradual, or even abrupt, abolition of traditional authority in the interior.

The claim by those in power that traditional structures, and in particular the traditional authority of Maroons and Indigenous peoples, hinder the development of their territories is unfounded. How can a structure obstruct development that has never been initiated? Which traditional structures, for example, would prevent the establishment of quality education or adequate healthcare in the interior?

Traditional leaders have repeatedly called for the construction of more and better schools and for the establishment of proper healthcare facilities. Yet to this day, sufficient high‑quality educational and healthcare services are lacking in the residential areas of Maroons and Indigenous peoples. The few schools that do exist fail to meet Surinamese educational standards and provide children in the interior with education of inferior quality.

Another striking point in the military regime’s policy document is the assertion that “discrimination against wakaman and women in the interior must be eliminated.” This statement clearly demonstrates that the authors lacked understanding of the social structures of interior communities, particularly those of the Maroons. Wakaman are guests, including Konlibi (in‑laws). There has never been discrimination against wakaman or women. Interior communities continue to welcome guests warmly, including those from Paramaribo, often offering them free lodging, something not reciprocated.

In‑laws in Maroon societies may freely use the property of the family into which they have married, as long as they remain part of that family.

Regarding alleged discrimination against women: anyone from the so‑called civilized society of Paramaribo who is unwilling to learn about a community from within, yet presumes to judge it, is likely to draw incorrect conclusions. This is the case with those who claim that discrimination against women exists among the Maroons, such as the authors of the report. Maroon societies are based on a matrilineal system, meaning that children belong to the mother’s line, which also determines inheritance.

Centuries before women in Paramaribo were permitted to hold important positions, this was already common in Maroon societies. Since the formation of Maroon communities, women have held significant roles. They have long occupied positions of authority in both the religious sphere (as priestesses) and the administrative sphere (as Uman-Basiya), to whom the community listens. Since 1994, women have also been appointed as Kabiten (village community leader). It was only from 1980 onward that women in Paramaribo were granted the opportunity to hold administrative positions, such as minister, district commissioner, or supervisory official.

Traditional Maroon authority is a system of governance that is fundamentally based on legitimacy earned through ethical conduct, respected qualities, and demonstrated functionality within the community itself. For that reason alone, the government should support traditional authority. The decline in the authority of traditional leaders today is partly the result of reprehensible actions by individuals in the political‑economic power centers of Suriname and French Guiana. It is also influenced by the fact that a significant portion of the current generation of Maroons is abandoning its own culture and uncritically adopting undesirable behaviors from non‑Maroons.

It must further be emphasized that traditional authorities are administrators and maintainers of order within their communities, not development workers. Precisely for that reason, the government should create opportunities to deploy development workers alongside traditional leaders and order‑keepers to support the development of interior communities. To date, this has never occurred.

Between 1975 and 1977, the political leadership in Paramaribo squandered two billion Dutch guilders, the amount Suriname received from the Netherlands at independence as a “golden handshake”, on the West Suriname Project. The government sought to stimulate development in an uninhabited area by constructing a new city there. The parts of the interior where people actually live are still referred to by the government as “the distant Interior.” For Paramaribo, the interior is considered too far away and too difficult to reach to bring about genuine development. Yet it is apparently not too far to extract, or allow the extraction of, the interior’s natural resources, the profits of which benefit only a small group in the coastal region.

As noted earlier, the authority of the Gaanman and other traditional leaders has declined. Yet it should not be forgotten that for example the Okanisi Maroons still regard their Gaanman as Kusumanpa, the protector of the people, to whom they show respect and reverence. In 1990, when the internal conflict between the Surinamese army led by Dési Bouterse and the Jungle Commando (J.C.) of Ronnie Brunswijk, composed primarily of Maroon youth, reached its peak, Bouterse sent a video message to gaanman Gazon Matodja of the Okanisi Maroons, requesting that he use his authority as a traditional leader to persuade the Jungle Commando to cease hostilities. Gaanman Gazon Matodja summoned the leader of the J.C., Ronnie Brunswijk, urged him to stop the fighting, and he complied.

During the subsequent peace talks in Paramaribo, attended by gaanman Gazon Matodja, several other Maroon leaders, the leadership of the J.C., President Ramsewak Shankar, and Bouterse as Commander of the National Army, Bouterse had the J.C. leadership arrested and two members killed. It was not the Gaanman but the president who proved unable to assert his authority: he could not prevent his subordinate, Commander Bouterse, from killing his guests.

In 1992, a delegation of Gaanman travelled to the Netherlands at the invitation of the Committee for the Support of the Development of the Interior (C.O.O.B.), an organisation founded by Maroons and Indigenous peoples and chaired by me, with support from experts in various fields.

The purpose of the trip was to discuss the situation in the interior and to explore possibilities for development. The document Principles for Policy and Development of the Interior of Suriname, prepared by C.O.O.B. on behalf of the Gaanman, served as the basis for these discussions. In October 1992, the Gaanman also presented this document to the President of Suriname, hoping that the government would adopt it as a guiding framework for interior development. A senior official of the Ministry of Regional Development, Mr. O. Kemble, who was responsible for development in the interior, also received a copy from me in my capacity as chairman of C.O.O.B. Kemble made it clear that Paramaribo was not willing to cooperate in the development of the interior, even when the initiatives originated from the interior communities themselves. To this day, no action has been taken to promote the sustainable development of the interior.

15. Conclusion

As someone born in the interior of Suriname and as a Maroon historian, I arrive at the following conclusions:

- The political leadership in Paramaribo has, from the colonial period to the present, systematically undermined traditional authority, using unacceptable methods such as divide‑and‑rule tactics.

- The political unwillingness of Paramaribo—not the traditional leadership structure—is the primary reason why the interior has not developed.

- Despite external manipulation, traditional Maroon authority retained its legitimacy for a long time. From the late 1950s onward, however, change set in: the isolation of Maroon society was broken, education and modern technology—however limited—were introduced, and increasing numbers of Maroons settled permanently in Paramaribo, the coastal region, and later abroad. The former social cohesion gradually gave way to a more individualistic lifestyle, a process accelerated by the Bouterse–Brunswijk conflict.

- Traditional leadership is confronted with new circumstances and behavioural patterns for which it is not equipped, contributing to a further erosion of authority. In two Maroon communities, the situation has even arisen in which two Gaanman simultaneously claimed leadership over the same group: from 1992 to 2014 among the Aluku Maroons, and since 2018 also among the Saamaka Maroons. This phenomenon may likewise emerge in other Maroon communities in the future if they fail to learn from these developments.

- Traditional authority, however, continues to have both a future and a legitimate place. Maroons, particularly those living in the traditional territories, still rely on this authority and derive a significant part of their identity from it.

16. Recommendations

Traditional authority is grounded in a system of norms and values intrinsic to Maroon society. As long as Maroons adhere to this system and derive their identity from it, any external attempt to alter or undermine it will only lead to resistance and disorder. At the same time, Maroons must recognise that contemporary circumstances place new demands on leadership. If traditional authority is to remain a respected institution, one that national and international political actors must take seriously, for example in matters of land rights and the socio‑economic development of the interior, then the following measures are essential:

- Establishing the legal status of traditional authority;

- Defining the powers, responsibilities, and tasks of traditional leaders;

- Creating a joint consultative body between the central government and traditional authorities;

- Ending appointments based solely on hereditary succession; contemporary competency criteria must also be applied;

- As a transitional measure, each Maroon and Indigenous community should have an institution dedicated to the development of traditional territories. This institution should consist primarily of well‑educated Maroons and Indigenous people.

17. Bibliography

Beet, C. de, en R. Price De Saramakaanse Vrede van 1762. Geselecteerde documenten. BSB 8. 1982 Utrecht. ICAU. (1982)

Groot, S.W. de, Djuka Society and Social Change. History of an attempt to develop a Bush Negro community in Surinam 1917-1926, Assen. Van Gorcum & Co. (1969).

Ministerie van

Binnenlandse Zaken

en Justitie (Suriname) Beleidsnota van het ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en Justitie, Directoraat Districtsbestuur. Paramaribo (1982)

Pakosie, A.R.M.; Gazon Matodja, Surinaams stamhoofd aan het einde van een tijdperk. 1999 Stichting Sabanapeti, 1999, Utrecht

Pakosie, A.R.M.; Toponiemen, Hydroniemen en Oroniemen betreffende het stamgebied van de Ndyuka in zuid-oost Suriname. In: Siboga, jrg. 6, nr. 1, 1996

Pakosie, A.R.M.; Maroon leadership and the Surinamese state (1760-1990). In: Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law, No. 37-38/1996, special double issue, page 263-277. University of Birmingham, United Kingdom. (1996)

Pakosie, A.R.M.; Addres by Mr. André R.M. Pakosie, to the Conference on the contribution of traditional authorities to development, democracy, human rights and environmental protections: Strategies for Africa. National House of Chiefs (Kumasi), september, 6, 1994.

Scholtens, Ben Bosnegers en overheid in Suriname. De ontwikkeling van de politieke verhouding 1651-1992. Afdeling Cultuur-studies/ Minov, Paramaribo. (1994)

[1] Andre R.M. Pakosie. Born in 1955 in Diitabiki in the Tapanahoni region (interior of Suriname). Naturopath, phytotherapist (according to the tradition of the Maroons from the tropical rainforest of Suriname), Maroon historian, writer, poet, editor-in-chief of Siboga (the magazine for Maroon culture and history), chairman of the Maroon Institute Foundation Sabanapeti, Documentary filmmaker, Kabiten (traditional leader) of the Okanisi Maroons in the Netherlands from 2000-2012, Edebukuman (head and guardian of the Afáka syllabic script) since 1993, founder (1974) of the Dag van de Marrons. Bearer and guardian of the highest Maroon award, the Gaanman Gazon Matodja Award, Ridder in de Ere orde van de Gele Ster (Knight of the Order of the Yellow Star), Suriname. Made his debut as a writer in 1972 at the age of 17 with the book: De dood van Boni. Writes prose and poetry. Besides his own publications, he has also published in renowned journals such as ‘The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law’ (University of Birmingham, England), De Gids, NWIG (New West Indian Guide/New West Indian Guide), OSO (Journal of Surinamese Linguistics, Literature and History) and BSS (Sources for the Study of Suriname). Specialises in Maroon culture and history.

IMPRESSIVE THIRD SYMPOSIUM ON THE AFÁKA SCRIPT

By Secretariat of the Sabanapeti Foundation

On October 19, 2025, the ‘Third online Afáka Symposium’ was held under the title:

“The Mission of da Atumisi Afáka and the Current State of the Afáka Script.”

During a PowerPoint presentation, Edebukuman da André R.M. Pakosie took the participants on a journey through the fascinating history of da Atumisi Afáka, who designed 56 unique characters and various punctuation marks for the then largely illiterate Okanisi Maroon people.

The Edebukuman is the head and guardian of the Afáka script. Da André R.M. Pakosie is the fourth person to hold this position since the designer of the Afáka script, da Atumisi Afáka. Da Pakosie succeeded Edebukuman Alufaisi in 1993.

The Afáka syllabary allowed the Okanisi Maroons, who learned to read and write it at that time, to communicate with each other in writing.

Da Atumisi Afáka taught the script to both men and women. In Maroon culture, the transfer of knowledge is a lengthy process that requires patience and constant evaluation of intention and progress. Da Atumisi Afáka identified four stages in the learning process of the Afáka script:

- LEVEL 1: Focused on learning to read and write the characters.

- LEVEL 2: A deeper level, including the study of previously unreleased letters written by early Bukuman.

- LEVEL 3: Learners qualify as Afáka instructors. Upon successful completion, they are authorized to teach classes, lead workshops, and give lectures independently.

- LEVEL 4: Reserved exclusively for the future Edebukuman, who is selected and trained by the current Edebukuman.

Some of da Atumisi Afáka’s students kept the Afáka script alive by writing intensively. Thanks to their efforts, historical events, recipes, and the names of inhabitants of several villages from that period were recorded in the script. For example, da Alufaisi made it a habit to take notes in Afáka during meetings.

Sadly, da Atumisi Afáka fell seriously ill, and the script was not widely adopted by the Okanisi Marrons.

HOW THE OUTSIDE WORLD ENCOUNTERED THE AFÁKA SCRIPT AND HOW THE CATHOLIC CHURCH MISUSED IT

When one of da Atumisi Afáka’s students was hospitalised, Brother Bernard, a nurse, noticed him writing in and reading from a notebook. Curious, he informed Father Morssink, who immediately saw the Afáka script as a tool to spread Catholicism among the Okanisi Maroons. From that moment on, most Afáka texts focused on Christian themes, prompting many Okanisi Maroons to further distance themselves from the script, its creator, and his students. Da Atumisi Afáka was even rejected by his matrilineal family.